When Two Educators Go on a Date to Mount Vernon

What we saw, what we debated, and what it revealed about learning, democracy, and each other.

Preamble:

Our trip to Mount Vernon, home of George Washington, above the Potomac River, a few miles south of our nation’s capital, was meant to be a date.

Time together.

An escape from the work week.

But because we are partners and deeply passionate science and history educators, our “date” was also an opportunity to dive into Hamiltonian lore, examine a historical site, walk through a gently sloped forest, and, if the conditions were right, be inspired to incorporate our adventure into future professional practices (we are lifelong educators after all).

The plan was simple: A Hamilton-themed tour, followed by a self-guided walk around the grounds and a quick look inside the Mount Vernon mansion and onsite museum before scooting home for afternoon meetings and pickup duty

The universe, however, had other (lesson) plans.

As it turns out, the day we visited Mt. Vernon also coincided with Colonial Days, special programming intended for nearby elementary school children. Thousands of school children, along with their teacher and chaperone guides, in what could only be described as a pint-sized Mt. Vernon flash mob.

Kids were running around the grounds, rolling in the grass. Bouncing in and out of line

Chaperones chatting to each other, teachers clutching clipboards - a slightly frantic look in their eyes.

All in all, a less-than-ideal learning experience for the kids, and certainly not the romantic escape we had envisioned.

Nonetheless (and no shade to schools using Mt. Vernon as an opportunity to get kids out of the school building), we remained committed to our escapade and carried on with our itinerary.

The Chaos, the Kids, and the Question

Attending a thoroughly enjoyable Hamilton tour, visiting the African-American burial ground, and tiptoeing through the under-construction mansion, we couldn’t help but cross paths with students.

No doubt, they were having a good time (an important component of any trip away from the classroom); however, as educators, what we saw happening was disconcerting because, based on our observation, it appeared that little, if any, learning was taking place (or being documented).

Where were the trip packets?

The clipboards?

Heck, even the cell phone selfies?

And while Jared, ever the front-line educator, wanted to know,

‘How are students keeping a record of what they are doing, learning, or preparing to incorporate into what’s happening in the classroom?’

Yom’s immediate reaction was, ‘Why is no one managing the space, the flow, the experience?’

For anyone who has read Jared’s Substack or his book, it’s no surprise that Jared feels that any trip out of the classroom should be structured as an academic investigation. Indeed, he feels that if students aren’t documenting, gathering data, or making meaning, they are simply being tourists.

Yom sees value even in the “messy” experience: “Sometimes the purpose is simply to expand a child’s thinking. You get on a bus. You walk the grounds. You realize that history is accessible, it isn’t just something written about in a textbook. It is a place and that matters too.”

So we stood there, observing (while trying to stay out of the way), and began to take our stances, framed our questions

What makes a trip meaningful? How much structure is necessary? Should all out-of-school adventures be designed as fieldwork, or (and when) does a simple field trip suffice?

The answers, of course, were nuanced. Both on the grounds of Mount Vernon and after we had returned home, our discussion unfolded—perspectives not always aligned, yet grounded in a shared understanding that what we observed during Colonial Days revealed opportunities for improvement.

And Then the Moment:

We both experienced it. Our responses in the moment and in reflection, revealed two different internal realities.

Yom’s Reflection

I was waiting for Jared to return from the restroom before we headed out. When we arrived, Jared had mentioned that he saw some students wearing “Trump” baseball hats. I took that information in and then filed it away. I looked up and a boy—maybe twelve or thirteen—walked past wearing a bright red MAGA hat. I squinted, and I felt my head tilt to the side, because in my mind I couldn’t possibly be seeing what I was seeing. In a historic home built, sustained, and enriched by the labor of enslaved people. In the place where Washington wrote his Farewell Address warning against political factions. In a home later preserved by women determined to save it. During a government shutdown. Surrounded by children of color who may or may not have known him, but who suddenly had to share space with the symbol on his head.

My reaction was immediate and visceral—affront, disappointment, anger, and a deep, familiar ache. Because if I, as a forty-something Black woman with language, context, and coping mechanisms, felt that jolt in my chest, what happens to the twelve-year-old child of color walking behind him or the one who turns to see him? What happens in their body? Where does their confusion or hurt go? And why should they or anyone else have to carry it at all?

I stood there thinking: How could a school allow this? Not as a First Amendment question—that’s too easy—but as a question of responsibility and community. In this political and racial climate, how could a school send children into public learning spaces without a clear boundary around symbols that dehumanize? Free speech has context. Children deserve protection, and adults have an obligation to safeguard their learning environments. When schools avoid taking a stance, they don’t stay out of the conflict— they are not neutral- they simply shift the burden onto the very children (or adults) most likely to be harmed.

Jared’s Reflection

As disconcerting as it was to be in the company of MAGA-hatted children on a field trip, my lens as a science educator—especially after leaving Mount Vernon—remained focused on the learning that was (or could have been) happening for kids in that moment. I kept wondering what students were meant to take away from the experience: what questions they had been encouraged to ask, what guidance they had been given, what structures might have supported or failed them in making meaning of the day.

Instead of offering a critique of the teachers who brought their classes to Mount Vernon’s Colonial Days—I didn’t have the full picture of their intentions or preparation—I kept returning to what I did observe. There was, at least from the outside, a lack of structure.

To me, fieldwork means active engagement: documenting, recording, and collecting evidence that will be used back in the classroom.

While taking students out into the world has inherent value—exposure to new environments, people, and ideas—the purpose of that exposure should be visible through student interaction and reflection. For the most part, this didn’t appear to be happening.

It felt like we were witnessing a missed opportunity to embody the three pillars of powerful fieldwork I write about in Learning Environment: Content (background knowledge), Context (the why), and Skills (what we do).

None seemed clearly in play.

Yet, what the day ultimately revealed to me is that learning in the field isn’t only about academic outcomes—it’s also about emotional and social context. Students learn not just from what we teach them, but from what we tolerate around and within their learning environment.

That realization, deepened by talking with Yom afterward, reminded me that: curiosity without care isn’t enough.

If we expect students to engage bravely with the world, we must ensure the environments we place them in honor both their intellect and their humanity.

And fieldwork, at its best, holds space for both.

Closing

Mount Vernon proved to be the ideal learning environment for two educators. We saw a lot of good, and we also identified areas that could benefit from improvement. The visit sparked conversation, reflection, and the kind of productive disagreement that enriches both teaching and partnership.

Indeed, when a teacher and their colleagues design a masterful field experience—one so intentional and engaging that it compels Jared not only to write a thank-you note but also to return to the same site of learning just days later—it raises the bar for what’s possible.*

It makes us wish that the students, teachers, and parent chaperones who visited George Washington’s home that day could have had an experience like the one our own child and their classmates enjoyed: purposeful, structured, and infused with genuine curiosity.

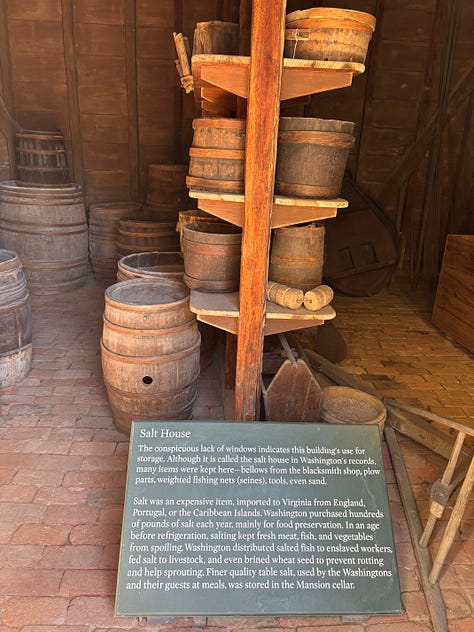

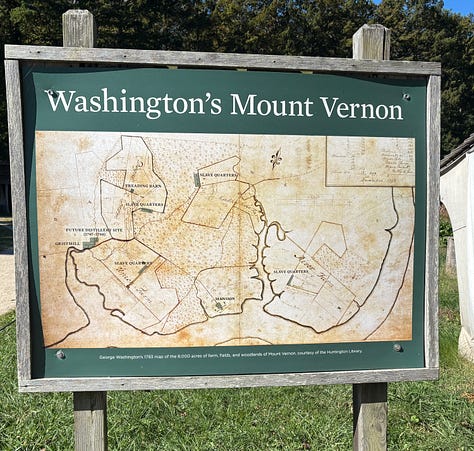

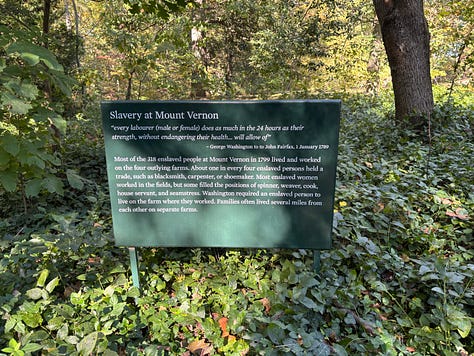

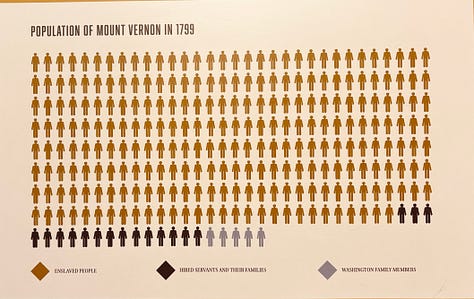

Imagine if the MAGA-hat-wearing children were asked to deeply interrogate the fact that our nation’s first president and his wife, Martha, owned a combined 317 enslaved people at the time of George Washington’s death.

Imagine if they had visited Mount Vernon’s African Burial Ground to sketch the string demarcating unknown gravesites or to craft honorary epitaphs for tombstones that were never laid.

Imagine if they had reflected on how the precedent Washington set—willingly stepping down from power—went largely unquestioned until the rise of MAGA.

Perhaps then, Mount Vernon would have left us feeling that the lessons of the past offered guidance on how to confront and one day overcome the very real and painful divides facing our country today.

Instead, our Mount Vernon exploration demonstrates that there is still much work to be done to ensure that all students feel safe beyond the classroom and have the opportunity to experience beautifully crafted, intellectually honest learning environments. .

Because we have done it in our own classrooms.

Because our own children and their classmates have experienced it in theirs.

Because this is the work we—and countless other educators—have dedicated our professional lives to continuing.

Because history provides lessons for the present, and because all students have the right to feel safe and to learn under exemplary conditions both inside and outside the classroom.

Extension (Optional and highly recommended)

So how do we get there? By designing fieldwork experiences that honor both intellect and empathy, beginning with a few simple shifts.

Love this perspective, it's so insightful to wonder how you might integrate that unexpected flash mob into future lessons, brillant as always!